By Haley Sweetland Edwards, The New York Times

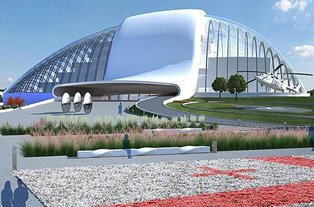

KUTAISI, Georgia — It took me more than three hours last Thursday to get from the center of Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital and commercial and cultural hub, to the country’s brand new Parliament building, a stadium-sized oyster-shell-shaped building enmeshed in steel netting. That’s because the Georgian Parliament is being relocated to Kutaisi, this small country’s second-largest city, some 150 miles west.

Parliament’s official move, which was announced last summer, is expected to take place this year, perhaps as early as next month. The measure is ostensibly designed to encourage decentralization, relieve Tbilisi’s strained infrastructure, provide an economic bolster for Kutaisi and symbolically connect the country’s two historic halves. But it seems destined to further weaken Georgia’s already-feeble legislative branch just as the country enters a period of electoral instability. Parliamentary elections are scheduled for October, and presidential elections, which could bring Georgia’s first democratic transfer of power, are expected next year.

Bolivia, Myanmar, Nigeria and other countries have moved one or more branches of government out of their capital, relocated the capital itself or created more than one capital. These changes have often created bureaucratic and logistical nightmares as well as political tensions among provinces. Sometimes, as is suspected in the case of Georgia, the moves were a deliberate political ploy to weaken one region of the country, a certain branch of government or the political opposition.

Most Georgians have greeted this move with barely more than a collective shrug — just 51 percent favor it — according to a survey by the National Democratic Institute (pdf). Why? Some naysayers cite the unnecessary expense, and others worry about the practical challenges of traveling between Tbilisi and Kutaisi. The two cities are currently joined by a plodding six-hour train ride or a dangerous drive down what is mostly a two-lane highway overtaken by speeding semis, trundling farm equipment and meandering cows. (The government is working on building a new airport in Kutaisi and bolstering Tbilisi-Kutaisi flights.)

Other critics, including some Georgian opposition politicians, say there are nefarious motivations behind the measure. They accuse President Mikheil Saakashvili of banishing Parliament to the far west in order to further marginalize it and discourage popular protest movements like those that have occasionally convened in recent years in front of the legislative building in central Tbilisi. Saakashvili himself came to power during the Rose Revolution of 2003 after his supporters stormed Parliament.

It wouldn’t be the first time a decision to relocate the legislature had been politically motivated. At the tail end of Augusto Pinochet’s rule in 1990, the government of Chile moved Parliament out of Santiago, the epicenter of the country’s commerce, culture and government, to Valparaiso, some 100 miles away. Although the move succeeded in bolstering Valparaiso’s economy, it is now, after two decades’ experience, largely considered to have been a mistake.

Peter Siavelis, the director of the Latin American and Latino Studies Program at Wake Forest University, told me by phone from Santiago last week that moving Chile’s Parliament had done little to decentralize power and a lot to create inefficiencies, like time wasted and increased traveling costs for legislators shuttling between Santiago and Valparaiso.

“By moving the legislature away from the rest of the government, a forum for informal politics was taken away,” he also said. This weakened Parliament. “If delegates can’t just walk over to, say, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and say, ‘Let’s talk about this piece of legislation,’ that has the effect of making them less influential.”

In Georgia, where tensions between the ruling party and the opposition have reached a seething crescendo this election year, it’s hard to look at the decision to relocate Parliament without suspicion. It’s simply too difficult to see how the move could help Georgia’s tottering democracy develop what it needs most: robust institutions and more diverse representation in government.

Original text