Foreign Observers about the Municipal Elections: “Even Though Formally the Elections Followed Democratic Procedures, Democracy Is not Really in Place in Akhalkalaki.”

June 1, 2010

30 May 2010

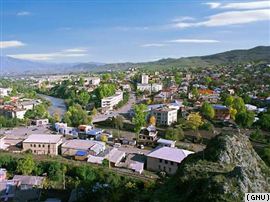

(Akhalkalaki, 31 May) A delegation composed of two representatives of the Norwegian Helsinki Committee and one from the Austrian Helsinki Association, registered as local observers with the Georgian Human Rights Center in Tbilisi, and observed elections in the southern Javakheti region in the period 29 to 31 May.

(Akhalkalaki, 31 May) A delegation composed of two representatives of the Norwegian Helsinki Committee and one from the Austrian Helsinki Association, registered as local observers with the Georgian Human Rights Center in Tbilisi, and observed elections in the southern Javakheti region in the period 29 to 31 May.

The delegation had meetings with local candidates, party and ngo representatives, election officials and voters during the weekend, including after the elections. On election day, the delegation visited nine polling stations in the Akhalkalaki and Ninotsminda electoral districts, one polling station during the opening, and one station during the count.

During the elections, Georgian voters elected 63 municipal councils (sakrebulos) and the mayor of Tbilisi (winner was Gigi Ugulava of the ruling National Movement), who was elected directly for the first time. The elections were administered by a three-tiered structure consisting of a Central Election Commission (CEC), 73 District Election Commissions (DECs) and 3619 Precinct Election Commissions (PECs).

Elections were held under a mixed system. Voters cast two ballots, one for party lists and another for the local majoritarian candidate. In the case of the Akhalkalaki sakrebulo, 10 seats where distributed among the parties on a proportional basis (with a treshold of 5%), and 22 seats were allocated to the candidates from single mandate constituencies. Both Akhalkalaki and Ninotsminda districts are mainly populated by Armenians, with some Georgian and Russian (Dukhobor) inhabitants.

General impression

The result of the party list elections in polling station 66 in Akhalkalaki, where the observers stayed for the count, was that the ruling national movement gained 97% of the valid votes. Although there was no evidence of large scale fraud on election day, this result, which was echoed by results in other precincts in the district, indicate that even though formally the elections followed democratic procedures, democracy is not really in place in Akhalkalaki.

The main irregularities were connected with pressure against opposition candidates, representatives and observers before the elections. Moreover, the presence of election material from the ruling party and, especially, of unauthorized persons at the polling premises may have created undue pressure on voters. In one instance in the village of Ptena, an unauthorized person directed the PEC and ‘assisted’ a voter inside the polling booth.

Violations and irregularities

The election law

The single mandate constituencies are defined by law, and based on tradition and geography, according to a senior member of the ruling National Movement. In the Akhalkalaki district this means that electoral units varies in size from 238 voters to 6867 voters, i.e. a vote in the smallest unit was equal to approximately 30 votes in the largest unit. The two smallest constituencies consist of the villages Chunshkha and Ptena, where less than two hundred and fifty voters elect one seat each in the sakrebulo. Both of these villages are ethnically Georgian, making some of the Armenian voters and officials complain of an ethnic bias in the delineation of single mandate constituencies.

The run up to the elections

In the Akhalkalaki district, we received a number of complaints from opposition party representatives relating to threats and pressure against their candidates, observers and PEC members. In particular, the Conservative party (number 7 on the party lists), which was perceived as the main opposition party, presented a number of cases. While we were unable to investigate all of these cases, the ones we did look into were credible.

Several of the no 7 candidates withdrew from the majoritarian race, allegedly after being threatened with repercussions against them and their families, who would stand to lose their jobs and places of study if the candidates did not comply. A candidate, who asked not to be identified and who did not lodge an official complaint, explained how he was called in to the office of his boss and explained that he should withdraw from the race, since the security service had threatened him (the boss).

One of the former candidates, who also asked not be identified, explained to us in detail how he was apprehended by officials from the security services in Akhalkalaki in early May. The security service officers identified themselves, and asked him to sign a statement to withdraw from the race in a way he found threatening and intimidating. He withdrew from the race. His story was confirmed to us by a number of witnesses. Asked why he did not lodge a complaint with the police and courts, he explained that as it was the authorities who were threatening him, it was no use to go to the same authorities for protection.

Apparently, these incidents contributed to the fact that the main opposition party was without candidates, observers and PEC members in several of the 22 majoritarian constituencies in Akhalkalaki. When asked why only the national movement candidate and a candidate from one of the so-called constructive opposition parties were standing for election in the village Diliska, a representative from the ruling National Movement joked that it was because the opposition members were afraid of getting a headache.

Election day

Unauthorized persons in the polling stations

The most disturbing feature in several of the polling stations we visited, was the presence of unauthorized persons in or outside the polling stations. Some of the people we saw at the polling stations in the town and villages of Akhalkalaki, were people we had previously seen at the National Movement headquarters. Although the atmosphere was generally orderly at the polling stations, it seemed that the ruling party had a visible presence at many of the polling stations, which could be interpreted as intimidating.

In the polling station number 54 in the village of Ptena (one of the small Georgian villages that elect a seat in the sakrebulo), a well-dressed man was present in the polling station during our visit there. During our interview with the PEC chairman, the man told the chairman what to answer. Later he went into the polling booth together with a voter. When we asked the PEC members who the man was, they said he was a PEC member. However, he was without ID, and when we asked him directly he said he was not a member.

Procedural irregularities

In general the atmosphere at the polling stations was calm and orderly, but it seemed that in many places the PECs were not aware of the correct procedures. During opening and closing of the polling stations, the prescribed procedures were not followed. However, these were not significant deviations from the election law.

There were isolated instances of family voting (polling stations 1 and 54 in Akhalkalaki). Campaign material for the ruling party was displayed prominently inside or directly outside at three polling stations. In polling station no 66, which had 375 registered voters, and a reported turnout of 278 voters, five signatures from voters were missing in the voters’ register.

Protocols

The opposition party number 7 representative, Armen Farmanyan, complained about protocols that had been changed and figures that had been changed during tabulation. We took photo evidence of one signed protocol with numbers that apparently had been changed (ps 44, Akhalkalaki), and one unsigned protocol with numbers that did not match (ps 48, Akhalkalaki) in a way that suggested that voter turnout had been inflated and the result changed.

News

December 13, 2023

Ethnic minorities outside the peace dialogue

November 6, 2023

‘Peace’ agenda of political parties

Popular

Articles

February 13, 2024