Why it is necessary to restore property rights to the Ossetian citizens affected in the 1990s?

April 17, 2022

Malkhaz Saldadze,

Associate Professor of Ilia State University

At the beginning of the 1990s when Georgia embarked on the path of formation of an independent state, our society was thrown into a turmoil of confrontations and conflicts. Dividing lines emerged both along the borders of the Soviet political and administrative units as well as between the public groups. The issue of the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia and the Autonomous District of South Ossetia, on the one hand, and the issue of belonging to ethnic and civil-political groups, on the other hand, became not only the subject of a dispute but the matter of violent confrontations and bloodshed.

Georgia has undergone two secessionist wars, a state coup, and civil war, and hosted several hotbeds of ethnic conflicts some of which show such examples of atrocities and brutalities that leave the sense of shame and regret when assessed from the human rights point of view. Among these are the facts of violations of the rights of the ethnic Ossetian citizens during the Georgian-Ossetian confrontation. Some may argue that the Tskhinvali separatists were committing no fewer offenses against the ethnic Georgian population. However, we have no place and objectives within this short essay to articulate the violence committed. Obviously, the violence was mutual, but the crime committed by one party does not justify the violence from the other side. All the more so as the facts of harassment of ethnic Ossetian citizens and the facts of their forced eviction were not limited only to the geography of the South Ossetian Autonomous District.

Ossetians live in the territory of Georgia even today outside Tskhinvali Region, would it be Shida Kartli, the capital, Kakheti, Samtskhe-Javakheti, or other regions. At the beginning of the 1990s, the harassment against Ossetians, dismissing them from their jobs and coercive displacement also concerned these regions. Many people affected by such violence moved to the South Ossetian Autonomous District, North Ossetia belonging to the Russian Federation, to Russia or other countries. The property created by them in Georgia is lost which may not be assessed only with tangible measurements forgetting about the symbolic and emotional measurements of the work and energy involved to build the property. The word “lost” for a reader may not mean the pain, trauma, and regret the same way as for “the person having lost things” which may not be measured by a tangible scale either.

The project launched by Human Rights Center The Dialogue over the Common Problems of Georgian and Ossetian Peoples is defined by legal and property issues, but it necessarily has the above emotional dimension, as it is aimed at ensuring justice.

Certainly, thousands of ethnic Georgians suffered from this conflict, and they also lost their property and lives. Who is responsible for them, who should provide justice for them? So far the answer is impossible to obtain on this issue. It is not hard to identify the party guilty of the disaster, but the party has also enough time and opportunity to think over the issue. In my opinion, at the time being, as there are public groups and organizations discussing the offenses committed against ethnic Ossetians, this means that time has come in Georgia to understand what has happened and meet those affected with fair attitudes. We cannot be that naive to believe that in our country everyone is of the same opinion and everyone understands the issue, either the acuteness for those affected or the relevance for the State which is in need to face the traumatic past.

Why is it necessary to return to the past and to revive the thing that no one “remembers”? The problem is that such experiences are never forgotten. The violence and offenses committed on behalf of the State leave traces not only in individuals who were the targets of the injustice but also a trace in eyewitnesses and perpetrators themselves. This trauma therefore belongs not to particular individuals and families who left their home country, lost their property, and do acknowledge whom to blame for this. This trauma generally belongs to the State of Georgia and its society, irrespective of the extent of awareness of all the public about the trauma. As long as the memory of violence is alive, not tied to one generation and a particular ethnic identity, there would always be prosecutors, their supporters, and people who feel guilty for this, creating with their shares of fear and unresolved anxieties the public attitudes or the models of behavior that would be reflected in self-defense, in a violent and aggressive mode that in turn creates an endless cycle of conflict and violence in public life.

To understand why it is necessary not only to be free from all of these but also to understand it, we are offering a small discussion concerning what does the public sphere mean and what impact does traumatic memory have on the public sphere. Therefore, we are offering a small sketch on how is it possible to understand the traumatic memory, to provide justice, and to revitalize the public sphere through such understanding and justice.

The State and the public sphere

Georgia has gained its statehood through blood and great sacrifice. On the one hand, this story is revealed through a heroic and romantic mantle, and on the other hand, this is the story of the misfortune of particular individuals. This is particularly true when it comes to the individuals who according to the mundane narrative of history, have not been made the heroes fallen for the sake of the State, but have been made sacrificial lambs. If we extend such judgments, ethnic Ossetians may be deemed as the “sacrificial lambs”. So, as the State was born under such content, the life of the State is described with words that have a similar meaning. Consequently, the State and the community creating the State consist not only from mere rules and management practices but is rather the environment of exchanging the emotional and irrational categories and has moral and symbolic content. Thus, neither is politics simply a power struggle, nor a practice of management. It is a constant fermentation process of the content in which there is a possibility to create public opinion which in turn is an immanent feature of the public sphere .

If we follow the assertions made by Jürgen Habermas that every conversation and assembly forming the public sphere, where general contents and perceptions are produced, provide for the concept of publicity, then the contents linked with common concerns that we create determine the quality of development and character of the public body of ours as the society. If the victims of the 1990s, meaning those individuals who lost their property and the emotional and symbolic capital linked to the property and are displaced to other countries, are not the subject of such discussions, it would mean that our public sphere lacks the compassion and sense of justice. It is obvious here a question emerges: do we want to be such a society? Consequently, the public sphere will definitely accommodate and process moral content and not only the political demands and decisions justified by the framework of rationality. Moreover, we have to take into consideration the fact that the public sphere has to be inclusive with regard to those who are deemed as “our” part, i.e. in the discussion about public and general, as noted by Habermas, should be included those whom we consider as “ours”. The following question is originated here: If we do not consider Ossetians affected by the war of the 1990s as “ours”, meaning those not from Tskhinvali Region where effective control of the Georgian authorities is not implemented, but those from other regions of Georgia, then who has the right to be “us” and who has not? This question, in my opinion, no longer concerns only Ossetians and quite possibly includes other groups with various identities. However, we have to focus in this case on Ossetians affected by the Georgian-Ossetian conflict. In this regard, one may suggest a point of view contrary to ours. Most of these people are now Russian citizens and from the political point of view they cannot possibly enter the debate sphere called “ours”. Nevertheless, if we return to the argument about emotional, moral, and symbolic interconnections, which in the case of Georgia is shown by memories left in the traumatized, separated families, relatives, and neighborhood communities, such a political argument becomes a technical obstacle. Despite the violent expulsion of the individuals from the political and economic sphere of the Georgian society, they retain the connection with this sphere through the offended sense of justice and the memories over it. Therefore, whether "us" can be formally a group based on citizenship, remains an open question. Further, the issue remains open whether the property rights can be discussed without these individuals? In my opinion, it is necessary to have them involved and to have their voices heard in the public sphere of Georgia, not only because there is a small part of the society that has a luxury of thinking and judging about justice, but this is required by the very principle of justice that is violated and that is to become the basis for "our" public life.

Obviously, the above judgment would face resistance with a view of the argument that the individual concerns, yet of the citizens of the foreign country and, even worse, of the country encroaching Georgian territories, cannot be the concern of “our” public sphere. To counter the above argument, besides the politically technical character of the issue of citizenship, let me focus on the features of the public sphere explaining the mutual character of issuing the benefits. Charles Taylor perceives such mutual character when determining the nature of modern society embedded in the core of the modern nation and State. He sees a change in the definition of moral order based on the horizontal character of mutual benefits, which distinguishes the traditional hierarchical structure of this process, where different types of benefits were collected and distributed through authorized social and political institutions (public groups, associations, social-political institutions, the Church, etc) . This means removing barriers of identities and some other technical barriers in the sphere of public discussion and orienting on what does private "me" and public "us" obtain, and therefore on to what extent the private benefits create general benefits. If we adjust this reasoning to the subject of our concern we would face a simple question: Although we are talking about people who have lost Georgian citizenship (not by their own will) and obtained citizenship of another country, mainly of Russia, what kind of benefits would the Georgian State and society receive? If we approach this from a purely academic perspective, the question can be followed by the whole cascade of questions: Who (and how) does benefit from this? How do they understand the benefits? How does this process of discussing about lost property determine the legitimacy of the government? And how and why do politics (the public sphere) require these discussions? Here, following the judgment of Taylor, a question emerges: Whether or not the transition from the vertical hierarchy to the horizontal mutual relations takes place and how does the latter determine the legitimacy of the political power of the State in the public sphere?

Of course, it is not a fact that the modernity and society in Georgia are mixed in such a manner. The rise of ultra-rights in the public sphere shows that prejudices and particular group values are also part of the public sphere and lead to collisions between different identities and political groups, and rationality and reasoning are not the only driving forces of the society. Consequently, resistance on the part of some individuals will be great against the recognition of offenses committed on ethnic grounds in the 1990s. This in turn invites the situation in which the trace of violence and its memory will be maintained and the public sphere cannot be transformed into a framework of relationships oriented at mutual benefits where the understanding of benefits would not be reflected only by tangible categories and will necessarily mean the supremacy of justice as a universal benefit. If we theoretically imagine that the State and the public sphere of Georgia are ready to consider and discuss and respectively satisfy the grievances of the Ossetians affected by the violence of the 1990s irrespective they hold or not Georgian citizenship, we can assume that some of the issues would be resolved:

1. Part of "our" inherent trauma would be accepted and acknowledged;

2. The anxiety of some of the groups of the public would be removed, including those of ethnic Georgians who are either witnesses or through relative connections share the same trauma, or were the initiators of the violence;

3. The burden of deepening the dividing lines in the public sphere and that of revolving around the conflict would be lifted.

These hypothetical benefits may be redistributed to each member of the society and public sphere in the sense that one post-conflict conversational and the painful topic would be over. This universal benefit may become only partially the basis for the collective catharsis and relief but with little change a great transformation begins that Georgia and our society have to go through.

Need to cure the public body of trauma

The attitudes to the events of the 1990s and their interpretations and perceptions of them change over time. Consequently, the voices of participants or witnesses of the traumatic events influence the lives of future generations. Not the event itself is being perceived but the image of the event coinciding with the narrative, that all the members of the society are ready to accept. Both trauma and memory operate as the basis for identity and exactly the crisis of identity is the source of trauma, and, on the other hand, the process of trauma brings forth the emergence of a new identity . Therefore, to manage the collective trauma, to "work it out", is one of the tasks of the public sphere; in case the trauma is managed, the public sphere acquires a particular character affecting in turn the political system. For example, as the efforts to suppress the trauma and to exclude the bearers of the voices of trauma grow, the more mobilized and less pluralistic would the public sphere be, and so the political system that would swing between democracy and non-democracy, or become steadily authoritarian.

To handle the traumatic memories and experiences bearing such memories and to detraumatize society, it is necessary to take specific steps and respectively promote a positive transformation. We need to have reflections in the political field of society and the public sphere, especially with those who are involved in the infrastructure of the representation of the trauma. First of all, it will be necessary to identify the actors who are either connected with the pains of Ossetian individuals or could represent their concerns. This means that it is necessary not only to allow those affected to the public sphere but also to work with those who are dealing with this sphere, for example, the politicians and the representatives of various media, including the representatives of visual and performing arts and cinematography, who are able to deliver the word to the relevant audience and facilitate the reflections. I suppose that working with such an environment is crucial because they are responsible for the reproduction of available languages reflecting the trauma, or they could be the creators of the new images or symbols changing the public attitudes toward the collective trauma. These assumptions are based on the approaches developed by Dominick LaCapra who elaborates about "acting out" and "working out” the trauma. For example, when imagining the traumatic events, we can often talk about “acting out” the trauma for specific political goals and not about "working out", that would help to recover the public body. When we multiply, "act out" a traumatic situation, we just live in the past, we do not analyze it, we just "imagine” it again. On the other hand, "working out" is connected with the revision of the situation, the liberation from prejudices, and the creation of a "new" reality . Therefore, a public reflection and discussion will be needed that would separate the situation from the “act out” approach; and also, it would separate the situation from the thinking mode in which one can always blame the victim due to the stereotypes and prejudices and place the victim within the frames of assessments such as: "instigator", "traitor", "separatist", "outsider" and so on. In this case, it will be possible to go deeper into the transformational framework of "working out", where it is necessary to consider the reality and facts and to face them: who has lost what, in what manner, and what kind of pain has been suffered.

For this purpose, as Jeffrey Alexander asserts, it will be significant to answer the following questions :

1. What is the source of the pain, specifically what has happened?

2. What is the nature of the victim who has suffered the pain: Were they separate individuals or particular groups of the society?

3. Whether there is a connection between the victims with a wider audience, with the whole community? For example, the pain of Ossetians belongs only to Ossetians, or the pain is extended to the public groups defined by other signs, such as mixed families, other ethnic groups, individuals and groups involved in violence, etc.?

4. "Working out" the trauma requires the answer to the question "who is to blame?" After the question is posed, the representation of trauma emerges taking place in the law (court hearings), literary or visual arts, scholarly articles (research and relevant publications), media, etc.

Discussion of these questions in the public sphere will allow the members of the public to think about how we talk about the victims and the trauma. One of the goals of public discussions may be to stimulate the contemplations about the obstacles existing in society related to revealing and representing the trauma . What hinders us from admitting the victim as a victim and from helping him/her to ease the trauma through emotional-symbolic (political gesture) and tangible compensations?

When dealing with the traumatic events of the past and their representations, it is also significant to understand the power of media and political elites in order not to allow for the instrumentalization of the fundamental aspects of collective identities as expressed in cultural trauma. The concept of cultural trauma itself implies that its subjects are not eyewitnesses or participants of a traumatic event. They are their descendants or representatives of future generations. It is important here to have the media capable not only to represent the trauma but also to measure and evaluate their responsibility in terms of the consequences of trauma medialization. This is another significant argument to think of why is it needed to understand and “work out” the traumatic events of the 1990s in general and specifically with relation to the Ossetian population.

When dealing with the traumatic events of the past and their representations, it is also significant to understand the power of media and political elites in order not to allow for the instrumentalization of the fundamental aspects of collective identities as expressed in cultural trauma. The concept of cultural trauma itself implies that its subjects are not eyewitnesses or participants of a traumatic event. They are their descendants or representatives of future generations. It is important here to have the media capable not only to represent the trauma but also to measure and evaluate their responsibility in terms of the consequences of trauma medialization. This is another significant argument to think of why is it needed to understand and “work out” the traumatic events of the 1990s in general and specifically with relation to the Ossetian population.

Therefore, it would be significant that the media correctly adapts the trauma representation to the historical events leading to an increase in credibility and emotional saturation of the discussion. We should also consider that this process is mutual. On the one hand, the media can transfer information about the traumatic events that otherwise would be unknown to the descendants. On the other hand, the media are actively involved in creating traumatic discourse, acting as a means of activation of trauma. In this case, the figure of a witness takes the leading role, which is just as necessary as the figure of an interpreter, as a precondition for representation and authenticity, which allows to refer at least to the trace of trauma, and allows to return to the suppressed memory source necessary for "working out" the trauma and recovery of the public sphere.

Finally, taking into consideration this another threat of medialization of the past, we may raise an issue of the motivation of the trauma representer and the needs of the society determining the traumatic discourse as constructed by the representer and society themselves. Representers (in our case NGOs and human rights activists) are oriented at mobilizing the public interests and maintaining the attention of the society on matters of public concern. Therefore the NGOs and human rights activists are mostly focused on the trauma. They make sure to get support from the political parties and engage various media in talks with the audience about the trauma. Consequently, they will have the task of encouraging the horizontal process of mutual benefits in the public sphere as outlined by Taylor. Their function is to support the public reflections as directed under the need of a healthy public sphere and universal moral criteria through understanding the old content and introducing the novelty. By all means, this will in turn affect the understanding of the moral criteria defining public good in the sphere of public discussions of the Georgian society and the State and the necessity to make relevant policies.

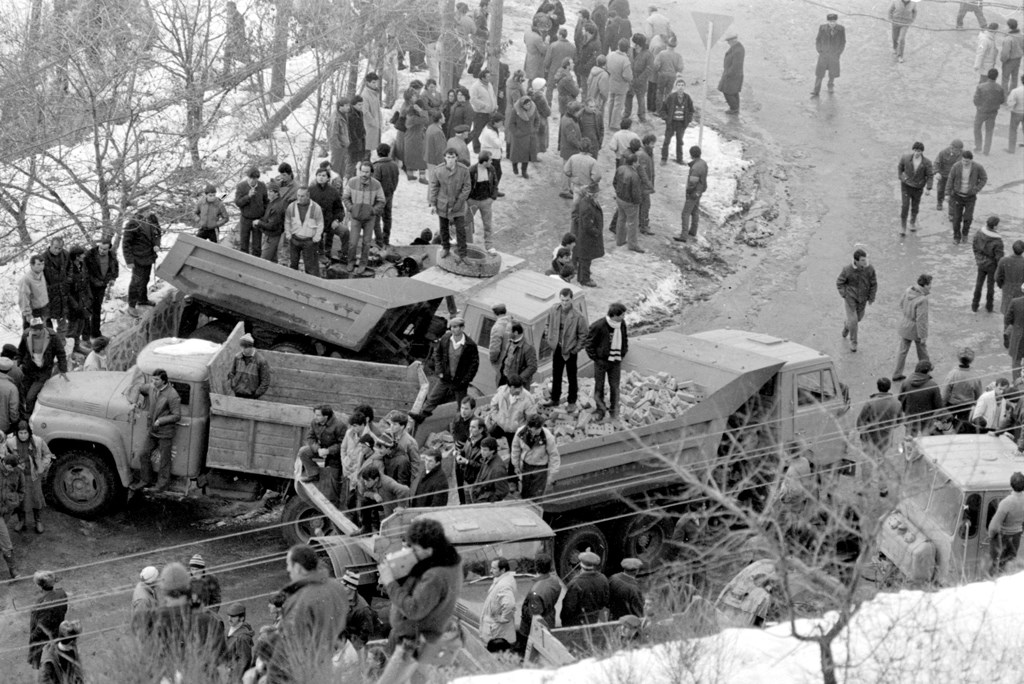

Photo by: Vladimer Svartsevich, from the archive of Anastasia Svartsevich

Photo by: Vladimer Svartsevich, from the archive of Anastasia Svartsevich

News

December 13, 2023

Ethnic minorities outside the peace dialogue

November 6, 2023

‘Peace’ agenda of political parties

Popular

Articles

February 13, 2024